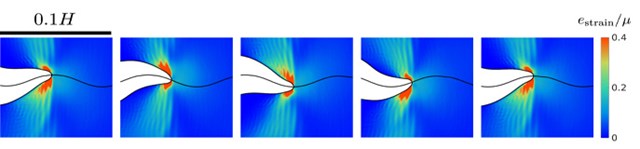

The trajectory of a crack tip, showing one cycle of oscillation. The horizontal wavy line shows the trajectory of the tip of the crack.

What happens at the moving edge of a crack?

It is said that a weak link determines the strength of the entire chain. Likewise, defects or small cracks in a solid material may ultimately determine the strength of that material – how well it will withstand various forces. For example, if force is exerted on a material containing a crack, large internal stresses will concentrate on a small region near the crack’s edge. When this happens, a failure process is initiated, and the material might begin to fail around the edge of the crack, which could then propagate, leading to the ultimate failure of the material.

What, exactly, happens right around the edge of the crack, in the area in which those large stresses are concentrated? Prof. Eran Bouchbinder of the Weizmann Institute of Science’s Department of Chemical Physics, who conducted research into this question with Dr. Chih-Hung Chen and Prof. Alain Karma of Northeastern University, Boston, explains that the processes that take place in this region are universal – they occur in the same way in different materials and under different conditions. “The most outstanding characteristic we discovered,” says Prof. Bouchbinder, “is the nonlinear relationship between the strength of the forces and the response taking place in the material adjacent to the crack. This nonlinear region, which most studies overlook, is actually fundamentally important for understanding how cracks propagate. Most notably, it is intimately related to instabilities that can cause cracks to propagate along wavy trajectories or to split, when one would expect them to simply continue in a straight line.”

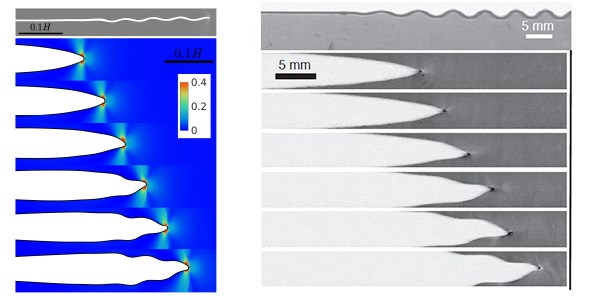

(l) A sequence of snapshots revealing the onset of the wavy (oscillatory) instability of ultra-fast cracks as obtained from numerical solutions of the new theory, in quantitative agreement with experiments. (r) An experiment in brittle polyacrylamide gel agrees with the theory. The experiment was performed in the laboratory of Prof. Jay Fineberg of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

By investigating the forces at play near the crack’s edge, Prof. Bouchbinder and his colleagues developed a new theory – published recently in Nature Physics – that will enable researchers to understand, calculate, and predict the dynamics of cracks under various physical conditions. This theory may have significant implications for materials physics research and for understanding the ways in which materials fail.

The onset of the wavy instability of ultra-fast cracks as obtained from numerical solutions of the new theory. The transition from a straight to a wavy trajectory occurs upon surpassing a critical velocity of about 92% of the elastic wave-speed, in quantitative agreement with experiments. The black line represents the crack surfaces and the color code represents the density of elastic energy in the non-broken material, where the hottest colors are localized in the non-linear region.

A crack propagating in a brittle polyacrylamide gel and undergoing a transition from a straight to a wavy trajectory upon surpassing a critical velocity of about 90% of the elastic wave-speed, in agreement with the new theory. The experiment was performed in the laboratory of Prof. Jay Fineberg at the Racah Institute of Physics, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel. Movie courtesy of Ariel Livne, Tamar Goldman, and Jay Fineberg.

Islands of Softness

Exploring a different topic, in a paper that recently appeared in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), Prof. Bouchbinder and a group of colleagues investigated the fundamental properties of the “glassy state” of matter.

The glassy state can exist in a broad range of materials if their liquid state is cooled quickly enough to prevent them taking on an ordered, crystalline state. Glasses are thus disordered, or amorphous, solids and include, for example, window glass, plastics, rubbery materials, and amorphous metals. Even though these materials are all around us and find an enormous range of applications, understanding their physical properties has been extremely challenging, owing, in large part, to the lack of tools for characterizing their intrinsically disordered structures and characterizing how these structures affect the materials’ properties.

Dr. Jacques Zylberg of Prof. Bouchbinder’s group, Dr. Edan Lerner of the University of Amsterdam, Dr. Yohai Bar-Sinai of Harvard University (a former PhD student of Prof. Bouchbinder’s), and Prof. Bouchbinder found a way to identify particularly soft regions inside glassy materials. These “soft spots,” which are identified by measuring the local thermal energy across the material, were shown to be highly susceptible to structural changes when force is applied. In other words, these soft spots play a central role when glassy materials deform and irreversibly flow under the action of external forces. The theory developed by the researchers thus brings us a step closer to understanding the mysteries of the glassy state of matter.

Prof. Eran Bouchbinder’s research is supported by the Rothschild Caesarea Foundation and Paul and Tina Gardner, Austin, TX.