REHOVOT, ISRAEL—December 13, 2011— Today’s announcement from the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN in Geneva points to promising signs for the existence of the Higgs boson. The LHC is the world’s largest particle accelerator. Researchers from the Weizmann Institute of Science have been prominent participants in ATLAS, one of the two LHC experiments (the other is the CMS, or Compact Muon Solenoid) to produce results in the search for this elementary particle. Prof. Giora Mikenberg was the ATLAS Muon Project Leader for many years and now heads the Israeli LHC team. Prof. Ehud Duchovni heads Weizmann’s ATLAS group, as well as a small group looking for signals that relate to supersymmetry (SUSY, which deals with possible solutions to theoretical problems). Prof. Eilam Gross is currently the ATLAS Higgs physics group convener. Each of these scientists, members of the Weizmann Institute’s Department of Particle Physics and Astrophysics, have been part of the effort to find the Higgs since 1987.

ATLAS and its sister project, CMS, have been searching for the Higgs boson, thought to be the particle that gives all the other elementary particles their mass. The Higgs is predicted by the Standard Model of particle physics, which provides a framework for all of the subatomic particles in nature. The Higgs is the one piece of the Standard Model that has not been proven to exist, and some scientists believe that the model will have to be rethought if the Higgs is not found.

Prof. Gross says, “In 2011, the LHC particle accelerator in Geneva collided over 300 trillion (a million million) protons. All of that enormous energy (7 trillion electron volts) went into the effort to produce the Higgs boson. But in each collision, other similar particles are created and there is no way to foresee what we will find. The chances of a collision producing a Higgs boson are so small that only about a hundred are expected to be observed over the course of a year.”

|

|

|

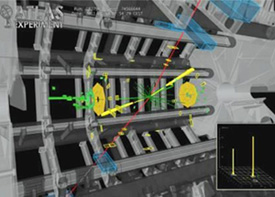

From the ATLAS experiments: Results of a collision that could represent a Higgs boson. |

|

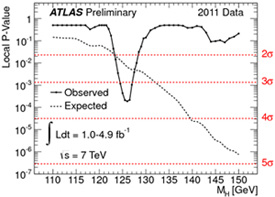

Finding possible signs of a Higgs involved looking for statistical anomalies in the data (compared to what the results would look like if there were no Higgs) in the expected mass range. The problem is that once these anomalies appear, the scientists had to rule out statistical flukes. But several weeks ago, it was noticed that “extra” events in the probable Higgs range had accumulated in the experimental results during 2011. States Prof. Gross, “We couldn’t believe our eyes—we looked at the screen for ages before we started to digest what we were seeing. In the past three weeks, the entire Higgs search team in the ATLAS experiment have checked and rechecked the results from every possible angle. We checked for errors … for bugs in the program.”

The ATLAS results suggest that there could be a Higgs boson with a mass of around 126 GeV (a GeV is a gigaelectronvolt, a unit of energy equivalent to one billion electron volts), and that there is just a 1 in 5,000 chance that the extra events observed in this particular mass are the result of a statistical fluke and not the creation of a Higgs boson. Such fluctuations might still disappear, so the proof is still not at all conclusive, but scientists believe that it bodes well for the next round of LHC collisions, set to begin in April 2012.

Prof. Ehud Duchovni’s research is supported by the Friends of Weizmann Institute in memory of Richard Kronstein; the Nella and Leon Benoziyo Center for High Energy Physics; and the Yeda-Sela Center for Basic Research. Prof. Duchovni is the incumbent of the Professor Wolfgang Gentner Chair of Nuclear Physics.

Prof. Eilam Gross’s research is supported by the Friends of Weizmann Institute in memory of Richard Kronstein.

Prof. Giora Mikenberg’s research is supported by the Nella and Leon Benoziyo Center for High Energy Physics, which he heads. Prof. Mikenberg is the incumbent of the Lady Davis Chair of Experimental Physics.