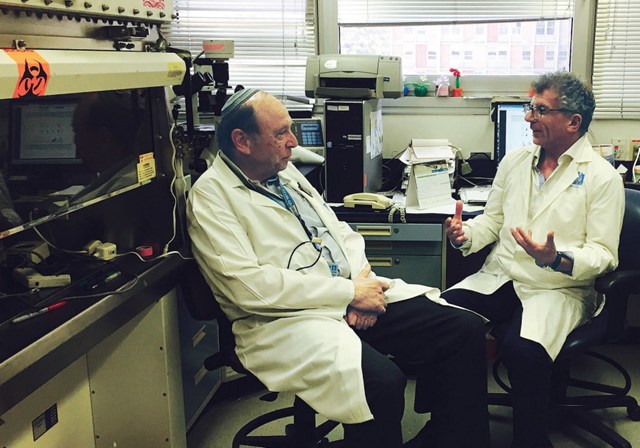

Prof. Reuven Or, from the Bone Marrow Transplantation and Cancer Immunotherapy Research Center, speaks with Pluristem CEO Zami Aberman last month. (photo credit:PLURISTEM)

Pluristem Therapeutics is developing a new therapy that could prolong survival and improve the quality of life for patients with damaged hematological systems

More than 13,000 Americans are diagnosed with myelodysplastic syndromes, a group of blood disorders associated with abnormal blood cell production. The average length of survival depends on the case, but the prognosis is often bad. However, according to Prof. Reuven Or, from the Bone Marrow Transplantation and Cancer Immunotherapy Research Center at Hadassah University Medical Center in Jerusalem, a new method that would prolong survival and improve quality of life for these patients is on the horizon.

Five years ago, Or tested a new methodology for assisting three patients who underwent failed bone-marrow transplants, injecting a simple shot of placenta-derived cells, into the thigh of each patient. The results were that their bodies started creating new blood cells, repopulating their blood system and improving their health.

“It worked in all three cases,” said Or, who administered the cells under the umbrella of compassionate use, which is the treatment of a seriously ill patient using a new, unapproved drug when no other treatments are available.

The cell therapy used by Or was developed by Pluristem Therapeutics. The company, based in Haifa, holds one of the most advanced manufacturing facilities in the world for the development of cell therapies. Founded using technology from the Weizmann Institute of Science and the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, Pluristem is using placental cells and its 3-D technology platform to develop cell therapies for conditions such as inflammation, ischemia, muscle injuries and hematological disorders. Several years ago, CEO Zami Aberman realized that the company’s technology could be leveraged even further, including for victims of radioactive catastrophes. The first experiments were done more than five years ago on small animals, in collaboration with Prof. Raphael Gorodetsky at Hadassah University Medical Center.

“At that time, it was just a dream,” Aberman told The Jerusalem Post. “Now, it is becoming a reality.”

PLX-R18 is now undergoing second- and third-stage trials in the US with the support of the US National Institute of Health, the department of defense and the Food and Drug Administration. A first iteration of PLXR18 focused on the treatment of people suffering from acute radiation syndrome could hit the market as early as next year.

Aberman said this approval could fast-track the cell product use for other indications relating to damaged hematological systems, including failed bone-marrow transplants, blood disorders because of prolonged chemotherapy or radiation treatment, and genetic blood disorders or related cancers. Collectively, this would mean improved treatment for millions of people.

Or explained that a person has three types of blood cells: red, white and platelets. Red blood cells carry oxygen to the body. White blood cells fight off bacterial infections and similar dangers. Platelets are responsible for coagulation, preventing internal bleeding.

While one can receive a blood transfusion to replace one’s red blood cells or platelets, one cannot transfuse white blood cells, making “the risk of life for people with low white cell count enormous,” said Or. “They get infections easily and they need antibiotics often – they can only survive this way for a limited time.”

Rather than using stem cells as a replacement part, PLX-R18 cells secrete a range of specific proteins that trigger the regeneration of bone marrow hematopoietic cells, thereby supporting the recovery of blood cell production.

Additionally, according to the Institute for Justice, at least 3,000 people in need of a bone marrow transplant die each year, because they cannot find a matching donor.

With PLX-R18, because the cells are grown using Pluristem’s proprietary 3-D micro-environmental technology and are an “off-theshelf” product, the process does not require the matching of tissues between donor and recipient, and may support the engraftment of an unmatched donor.

What makes PLX-R18 even more special is that it is developed from the “life-giving organ, the placenta,” said Aberman, who said the “18” in the product’s name stands for the Hebrew word “hai,” which means “life.”

Aberman, a mechanical engineer by education, got involved with Pluristem, because he wanted to try to improve the lives of those suffering from fatal diseases. His intuition told him to investigate the placenta. Today, the Human Placenta Project, a collaborative research effort launched by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, is helping the medical community to understand the role of the placenta in health and disease. However, when Pluristem got started, this was a largely untapped organ.

“Many assumed that the placenta did its job for nine months and then would just lose its potency,” said Aberman. “They thought the placenta would be dead after its nine months of giving life. When we brought it for investigation, we found that the opposite was true: the placenta is full of active, living cells.” He said that from one placenta collected after a cesarean birth, Pluristem can manufacture as many as 25,000 treatments.

Pluristem filed the first patent for its placenta research in 2006 and began the activities that ultimately led to PLX-R18.

“Just as the placenta is used to supply the fetus with what it needs to develop, so we use these same placenta cells to help the patient heal himself,” said Aberman. “We are not altering anything. Mother Nature gave the cells this ability. We are just using them.”

Or said in his dozens of years of work, Pluristem’s discovery is among the most exciting.

“It may have started with a few patients treated under compassionate use,” Or said. “But now there is hope that this could be an effective therapy for thousands more.”