Molecular geneticist Prof. Michel Revel has passed retirement age but is highly active in a company that hopes to cure diabetes and other chronic diseases.

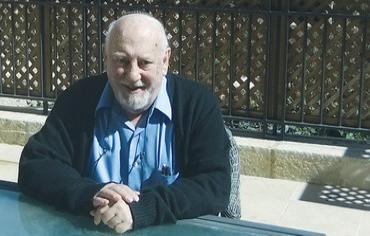

PROF. MICHEL REVEL. Photo: JUDY SIEGEL-ITZKOVICH

Six months after his 75th birthday, after teaching generations of young graduate and post-doctoral students at the Weizmann Institute of Science and with a wife, four children and 12 grandchildren, one could expect Prof. Michel Revel to sit back and enjoy life. Yet, the Frenchborn, internationally acclaimed molecular geneticist, who invented a major drug to treat multiple sclerosis used around the world and received the Israel Prize, EMET Prize and other major awards, has his eyes fixed on the future.

He is founder and chief scientist of Kadimastem, a three-year-old biotech company based in the Weizmann Science Park on the Ness Ziona-Rehovot border devoted to industrial applications of human embryonic stem cells. By testing therapeutic efficiency in functional human tissues, it is performing early drug-toxicity testing instead of using rodents in the lab for the discovery of new drug compounds in his and other labs for the devastating neurological diseases amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and multiple sclerosis (MS).

Aimed at promoting regenerative medicine (the development of tissues to replace those that are diseased), the company aims to produce pancreatic islets that produce insulin from pluripotent stem cells and implant them into the human body to cure type 1 and even type 2 diabetes. The main problem in reaching a regenerative medicine solution to diabetes, for example, is perfecting an encapsulation technique to prevent the patient’s immune system from attacking the implanted cells and ensuring that the right amount of the hormone is secreted according to blood glucose levels. Pluripotent stem cells may also be used to create new tissues to cure other devastating diseases. Cellcure, an israeli embryonic stem cell company created by Prof. Benjamin Reubinoff, aims at treating macular degeneration, which is a major cause of age-related blindness.

REVEL WAS born in Strasbourg during the rise of the Nazis in Europe to a Jewish family that had lived in France for generations. “It was Napolean who gave surnames to the Jews,” said the professor in a recent long interview with The Jerusalem Post. “Before that, Jews had proper names followed by the names of their fathers. Our surname may have come from ‘Raphael,’ which was changed to Revel, because that is a common name among non-Jewish Frenchmen,” he said in the living room of his splendid home in David’s Village with the magnificent view of Mamilla and the Jaffa Gate of Jerusalem’s Old City.

He and his Strasbourg-born wife Claire — a biophysicist-turned-travel agent when they came on aliya in 1968 — spend their weekends in the capital to be with their children and grandchildren and the rest in their Rehovot home to be near his work.

“My family were Holocaust survivors; as small children, we had to hide in the Alps, and after the war, went to Lyon and then back to Strasbourg. My father was a practicing physician and President of the Jewish Consistoire in Alsace. My wife’s mother survived deportation to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp,” Revel recalled.

Revel’s uncle — his mother’s brother — was the illustrious Prof. Andre Neher, a philosopher and scholar who after the Holocaust created the first chair of Jewish studies at the University of Strasbourg and later moved to Jerusalem, where he died in 1988. “He influenced me very much,” said Revel, who himself had completed his doctorate in biochemistry and medical degree at the University of Strasbourg in 1963 and then went to Harvard.

Michel then came to the Weizmann Institute of Science for his post-doctoral work.

Modern Orthodox with moderate political views and raised as a Zionist, the biochemistry professor decided with Claire after the Six Day War to come on aliya with their children.

“We didn’t leave France due to anti-Semitism. We had a strong feeling of Jewish identity. The war of 1967 woke us up with the realization that the place to be was in Israel. Now, most of my family members are here.”

Although he is an licensed MD, he never practiced as a physician. “I went immediately into research. I studied medicine mostly because of my father, but I found I didn’t have a bedside manner. You have to have a lot of patience to deal with patients.”

But two of his children do have such a gift.

One, Prof. Ariel Revel is a fertility specialist and head of ovum donation and egg preservation at Hadassah University Medical Center in Jerusalem’s Ein Kerem, while his daughter Dr. Shoshana Revel Vilk is the head of pediatric medicine teaching at the Hebrew University Medical Faculty, a Hadassah expert in pediatric hemato-oncology, as well as director of its pediatric hematology center. One son, Sammy Revel, is a career diplomat at the Foreign Ministry.

When Michel first came to Weizmann for post-doctoral research, he “didn’t get such a warm welcome. There was no real interest there in scientists settling in Israel. Many colleagues who were there went back to the US.

But after we settled here and I was given a permanent position, I felt part of it. I felt at home. There has always been a connection at Weizmann between basic and applied science.

One day a week could be devoted to industry- related research. Prof. Michael Sela was a great president of the institute then, and it was a great place to be. I have also worked at the Pasteur Institute in France and at Harvard. The Weizmann Institute is certainly of a high standard.”

Prof. Ada Yonath, an Israeli crystallographer at Weizmann who shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2009 and was born less than a year after Revel, gave him credit for getting her interested in ribosomes. Yonath’s work — on the structure and function of these “cellular machines” that convert the instructions found in messenger RNA into the chains of amino-acids that make up proteins — turned her into a Nobel laureate and made her the first Israeli woman to receive the chemistry prize.

“I did not intend to do research on multiple sclerosis,” recalled Revel. “I was interested in protein synthesis, the control of gene expression at the level of ribosomes.” This brought me to interferon, and its application in MS.

Also at Weizmann, Sela, Prof. Ruth Arnon and the late Dr. Dvora Teitelbaum were looking for what caused MS and got the idea that a copolymer could protect the central nervous system from demyelination, in which nerves lose their insulating sheathe, causing them to “short” like an exposed piece of electrical wire. This leads to periodic attacks in which parts of the body suffer weakness and pain. In the the majority of patients, the neurological attacks come and go suddenly, resulting in the relapsing-remitting form of MS.

After spending a few decades on developing the copolymer, they produced Copaxone — one of the Teva corporation’s most profitable and effective drugs.

Between the 1970s and 1980s, Revel and his team, however, took a different approach.

They began to study interferons — proteins created and released by host cells in response to the presence of viruses or other pathogens.

These allow for communication between cells to trigger the protective defenses of the immune system that eradicate these pathogens.

Interferons are named for their ability to “interfere” with the multiplication of viruses within their host cells. Revel’s group studied interferon-beta, a form made by most cells in the body and which in addition to its antiviral effect also regulates immune cells so that they will not cause an auto-immune reaction against the body own tissues. Such a harmful reaction is a cause of MS.

Revel’s lab created a recombinant DNA form of the interferon gene which they introduced into animal cells, forcing them to efficiently secrete the interferon beta glycoprotein, as it is found in the human body. Called interferon beta-1a (recombinant interferon 1a), it was given the commercial name of Rebif — still today the number one blockbuster product of the Merck-Serono pharmaceutical giant, used for treating relapsing- remitting MS.

Thus two of the leading MS drugs in the world were both developed at the Weizmann Institute of Science. Rebif is now sold in pre-filled electronic syringes for injection under the skin three times a week. “Based on our molecular studies, we showed that it’s most effective when give three times a week.

Working on Rebif, my team was one of three groups in world that discovered interferon’s molecular mechanism of action,” he noted. “We found that interferon beta- 1a is also useful against papillomavirus genital warts that can lead to cervical cancer and against recurrent herpes.”

His work led to the establishment in 1979 of Inter- Pharm-Serono, the Israeli biotech company that developed the industrial productionof Rebif and where he worked as its chief scientist one day a week while continuing his research at Weizmann.

Another injectable interferon beta-1a Interferon beta-1a, called Avonex (also under Revel’s patent), is produced by the Biogen company, while a third brand called Betaferon is made by Schering AG. He is not deterred by the fact that three different and competing interferon beta drugs are given for relapsing- remitting MS; patent-protection of the three have already expired, but profits are still being made. “Treating the many MS patients over the world requires several companies.”

Many researchers aim to do research on various topics and publish paper after paper, he continued. “This makes it easier to climb the academic ladder faster to full professor.

But,” Revel said, “if you want to concentrate on developing a drug, or several drugs, that will treat patients, you have to take the longer route of industry. It’s exciting to think that hundred thousands of people are taking your medication.”

More could benefit since if relapsing-remitting MS is treated early with one of these drugs, you can even prevent it from going further, “You give it to the patient immediately after a first episode, and confirmation of the diagnostic by an MRI scan showing white spots of demyelinization in the brain.”

Unfortunately, there is a progressive form of MS, which usually kills its victims in the end and has no effective treatment. “In the progressive form, these MRI white spots cannot be seen. This type affects about 10% of patients. It results from an degenerative disease in which the death of nerves is more important than the loss of myelin covering on the nerves. It isn’t clear why the nerves die.

Some scientists even think the progressive form is a different disease. It is more like ALS, which causes loss of motor neurons and muscle function.”

WHEN REVEL reached the age of 72, the tenth Weizmann president, Prof. Daniel Zaijfman, asked him to close his lab. “I wanted to start a new company. The president’s policy was if you want to continue working in science, you have to leave the institute. He said he couldn’t let everybody work; one had to give young people a chance. So I am a professor emeritus, after 40 years as full professor, and I have an office at Weizmann, but I spend most of my time at Kadimastem. It’s better to work in science than to sit in an office as an emeritus.” Five researchers with a Ph.D. from his group left Weizmann to work with Revel at Kadimastem.

At the new stem-cell company Kadimastem, that he cofounded with an entrepreneur, Yossi Ben Yossef, “we have program working on ALS. The strategy is to use neuroprotective cells (astrocytes) produced from pluripotent stem cells, as a cell therapy for ALS. Merck Serono, he continued, has contracted with Kadimastem to develop a new drug for MS by screening small molecules that could be effective. We already found small chemical molecules that stimulate the human myelin-forming cells derived from our stem cells.

As for diabetes, whose two types affect around 400 million people around the world and is due to encompass almost 600 million by 2035, could be cured if the need for insulin injections and various oral medications are made unnecessary. Revel dreams of doing this using pluripotent stem cells. “Using these, one can make an unlimited amount of cells and then start differentiation into any type of human tissue you want. One must have a protocol to push them into each different direction,” explained Revel.

For insulin-dependent diabetes, pancreatic islets are produced from the stem cells at Kadimastem.

“Already today, islets are taken from corpses to treat diabetes, but there are not enough such organ donations so that only a small number of diabetics — maybe one percent — benefit. The stem cell industry aims to produce enough islet cells for both type-1 diabetics and the third of type-2 diabetics who need insulin to balance their blood sugar (over 130 million patients worldwide). The cells would not,” Revel said, “have to reach the pancreas but could be put anywhere under the skin — using a small incision — or in the abdominal cavity, wherever there is blood flow. The cells would sense how much insulin is in the flood and secrete as much insulin as needed. We have animals in our lab in which the implants have survived for six months.

We think they could last for a year or two and then be replaced.” Kadimastem’s islet cells also produce glucagon — a peptide hormone secreted by the pancreas that raises blood glucose levels, having the opposite effect of insulin, which lowers glucose levels. Glucagon producing cells could prevent hypoglycemia — a medical emergency that could even be fatal — in diabetics.”

The islets would be “imprisoned” in a polymeric capsule that wouldn’t allow the body’s immune system to reject the tissue. It has to be porous enough to allow the glucose in and the insulin to come out, said Revel. This is the trickiest part; “now we are in the preclinical stage, working on mice. Our plans are to continue for three years until we get to phase-1 trials. So obviously, the stem-cell islets won’t appear tomorrow.

“Ours is a public company, with private investors. We went public on the Tel Aviv stock market a year ago. It isn’t easy to get investments, but we have grants from the Economics Ministry’s chief scientist office for three years,” said Revel.

Kadimastem doesn’t have a monopoly on the insulin-producing idea, however. “There are companies in California, and they have $3 billion for embryonic stem cell research. There is also one in Canada — part of Johnson & Johnson. They all invested much more than we did, but they are struggling with the same problem of encapsulation that we are. There are still a lot of difficulties to solve, but in some aspects we are farther ahead. We may be the only one that has the industrial technology to make humanislet cells that respond to glucose. We don’t worry about competition, as each 1% of the insulin market is $1.5 billion. No one company can capture the whole market,” said the company’s chief scientist.

Revel also discovered interleukin 6 (IL6), which has many functions, but that he showed helps nerve survive. In animals, low dose IL6 is effective to treat neuropathy (nerve dysfunction often painful) caused by diabetes and by chemotherapy. With Geneva-based scientists, clinical trials of IL6 in neuropathy are about to be initiated this year, and will hopefully confirm the usefulness of this protein in medicine.

AS AN observant Jew, Revel has long been interested in medical ethics, and he was for 13 years a member of the UNESCO International Bioethics Committee, as well as chairman and a member of the Israel National Bioethics Committee. He helped set down policy on surrogacy, organ donations, preimplantation genetic diagnosis of embryos and egg donations. Even today, he gives a lecture on Kabbalah and Hassidism in Rehovot. “It keeps me active thinking about Judaism and science.”

Michel Revel clearly has enough to keep him busy for the next 75 years.