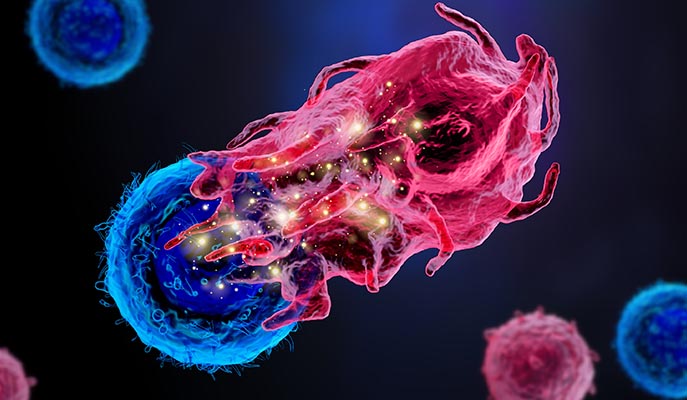

The yellow sparks illustrate intracellular processes that can be detected using INs-seq when two cells – for example, a T cell and an immune suppressor cell – interact

REHOVOT, ISRAEL—August 10, 2020—Invading cells’ private space – prying into their internal functions, decisions, and communications – could be a powerful tool that may help researchers develop new immunotherapy treatments for cancer. As reported in Cell, a research group at the Weizmann Institute of Science have developed a technology enabling them to see inside tens of thousands of individual cells, at once, in greater detail than ever before.

The group, headed by Prof. Ido Amit of the Department of Immunology, applied this method to define the immune cells that infiltrate tumors, identifying a new subset of innate immune cells that “collaborate” with cancer. Blocking these inhibitory immune cells in mice greatly enhanced the anti-tumor immune response, killing the cancer.

Prof. Amit and his group had previously made significant inroads into seeing inside cells when they developed single-cell RNA sequencing – a means of sequencing all the RNA in thousands of individual cells at once. The new technique, called INs-seq (intracellular staining and sequencing) – developed in Prof. Amit’s lab in a project led by research students Yonatan Katzenelenbogen, Fadi Sheban, Adam Yalin, and Dr. Assaf Weiner – enables scientists to measure, in addition to the RNA, numerous proteins, processes, and biochemical pathways occurring inside each of the cells. To do this, they had to develop new methods of getting inside the cell membranes without harming the genetic content. This wealth of “inside information” can help the researchers draw much finer distinctions between different cell subtypes and activities than is possible with existing methods, most of which are able to measure surface proteins only.

In fact, Prof. Amit compares those existing methods of cell characterization with buying watermelons: They all appear identical from the outside, even though they can taste completely different when you open them up. Distinguishing between subtypes of cells that seem identical from the outside, such as inhibitory immune cells versus effector immune cells, may be crucial to when it comes to fighting off cancer.

Although the principal groups of immune cells had been identified many decades ago, there are hundreds of subtypes that haven’t been classified and that have many different functions. “Specific immune subtypes, for example, may play a role in promoting cancer or enabling it to evade the immune system, provoke tissue destruction by overreacting to a virus, or act mistakenly in autoimmune syndromes, attacking our own body. Until now, there was no sufficiently sensitive means of telling these apart from other subtypes that appear identical from the outside,” says Sheban.

In order to sort through these different immune functions inside tumors, the Weizmann scientists used their technology to address issues that researchers had been trying to resolve for decades: Why does the immune system fail to recognize and kill cancer cells, and why does immunotherapy for most tumor types often fail?

In searching for answers, the team asked whether cancers might hijack and manipulate particular immune cells to “defend” the cancer cells from the rest of the immune system. “The suspicion that some kind of immune cell might be actively ‘collaborating’ with cancer is not as strange as it seems,” explains Yalin. “Immune responses are often meant to be short-lived, so the immune system has its own mechanisms for shutting them down. Cancers could take advantage of such mechanisms, enhancing the production of the ‘shut-down’ immune cells, which, in turn, could prevent such immune cells as T lymphocytes that would normally kill them from taking action.”

Indeed, the team succeeded in identifying T-cell-blocking immune cells, which belong to a general group known as myeloid cells: a broad group of innate immune cells that mostly originate in the bone marrow. Although this particular subset of suppressive myeloid cells was new, it was distinguished by a prominent signaling receptor that Prof. Amit and his group had seen before called TREM2. This receptor is critical for the activity of the cells that block the actions of tumor-killing T cells; normally, cells bearing this receptor are crucial for preventing excess tissue damage after injury or calming an inflammatory immune response. But Prof. Amit had also come across a version of this receptor in other immune cells involved in Alzheimer’s disease, metabolic syndrome, and other immune-related pathologies.

The group’s next step is to develop an immunotherapy treatment using specific antibodies that target this receptor and could prevent these immune-suppressive cells from supporting the tumor. “Because this receptor is only expressed when there is some type of pathology,” says Dr. Weiner, “targeting it will not damage healthy cells in the body.”

Preliminary evidence for the TREM2 therapeutics was demonstrated by the scientists in mouse models of cancer with genetically ablated TREM2 receptors. In those mice, tumor-killing T cells “came back to life” and attacked the cancer cells – and the tumors shrank significantly. If treatment based on this finding is, in the future, proven effective for human use, it might be administered on its own or in combination with other forms of immunotherapy.

Yeda Research and Development, the technology transfer arm of the Weizmann Institute of Science, is currently working with Prof. Amit to develop this immunotherapy antibody for clinical use, and there has already been a great deal of interest in INs-seq technology. “Clarifying the mechanisms of autoimmune and neurodegenerative diseases, and answering the question of why the immune system often fails in its fight against cancer or why most patients do not respond to existing immunotherapy – all of these may come down to specific actions of subsets of immune cells. We believe INs-seq may help researchers identify those particular cells and develop new therapies to treat them,” says Katzenelenbogen.

Also participating in this research were Ido Yofe, Dmitry Svetlichnyy, Diego Adhemar Jaitin, Chamutal Bornstein, Adi Moshe, Hadas Keren-Shaul, Merav Cohen, Shuang-Yin Wang, Baoguo Li, Eyal David, and Tomer-Meir Salame, all of the Weizmann Institute of Science.

Prof. Ido Amit’s research is supported by the Helen and Martin Kimmel Award for Innovative Investigation; the Sagol Institute for Longevity Research; the Kekst Family Institute for Medical Genetics; the Thompson Family Foundation Alzheimer’s Research Fund; the Adelis Foundation; Richard and Jacqui Scheinberg; the Ben B. and Joyce E. Eisenberg Foundation; the Anita James Rosen Foundation; the Lowy Foundation; the Wolfson Family Charitable Trust; the Vainboim Family; Lady Michelle Michels; Rosanne Cohen; Mauricio Gerson; Erika Mogyoros; Thomas Franklin Buchheim; Jeff Pinkner and Maya Iwanaga; the estate of Simon Saretzky; and the estate of Arthur Rath. Prof. Amit is the incumbent of the Eden and Steven Romick Professorial Chair.